How far would you go to break free from a system responsible for your oppression?

How far would you go to break free from a system responsible for your oppression?

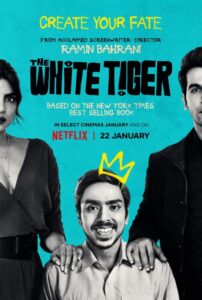

“The White Tiger,” based on the book of the same name, examines this question through the cynical tale of Balram Halwai (Adarsh Gourav).

“The White Tiger,” available to watch on Netflix, was released in theaters on Jan. 13.

The narrative shifts between the years 2000, 2007 and 2010 to explore the various stages of Balram’s life.

As a child, Balram had potential. He excelled at reading and writing, but because of a family tragedy, he was forced to stop going to school and work in a tea shop.

Still, Balram proves himself to be intelligent and observant.

He listens to the patrons of the shop as he crawls around to clean the floor, and he learns there is good money to be made as a driver for wealthy families.

Balram goes to the gates of the village landlord’s sprawling mansion and manages to score a job as the family’s second driver.

He answers primarily to Ashok (Rajkummar Rao), the landlord’s wealthy son.

Ashok needs to travel to New Delhi for political business, so Balram is the one who drives him.

It is the place young Balram dreamed of living in.

When he arrives, he finds a city vastly different to what he imagined as a child; Ashok and his wife Pinky (Priyanka Chopra) stay in the beautiful, pristine hotel while Balram stays in the dingy, cold basement next to the parking garage.

It is here that the relationship between Ashok and Balram is evidently complicated — sometimes, Ashok treats Balram like a friend. He tells Balram to stop calling him “sir,” and they play video games together.

Other times, though, Ashok and his wife, Pinky, mock him, still clearly thinking of him as inferior.

Despite this treatment, Balram still goes out of his way to be as good of a servant as possible, using his hard-earned money to buy a new work shirt when his is stained or no longer eating his favorite food because Pinky doesn’t like the way it smells.

Balram places his masters above himself. Unquestioningly.

This changes when Pinky hits a child with the car, and Balram is forced to take the blame. In this moment, Balram finally realizes that to Ashok, he is disposable.

In the second and third act of “The White Tiger,” we watch the transformation of an eager-to-please, compliant servant into a well-dressed and cunning entrepreneur.

Stylistically, “The White Tiger” is a triumph. It has distinct and beautiful visual flare. The establishing shots of each new setting ground the viewer, drawing them further into the narrative.

The film explores the personal dynamic of a master and his servant, which adds nuance to the questions it is asking about societies on a larger scale.

Who is responsible for the violence committed because of an unjust system? Is it the people who uphold the harmful status quo, the oppressed or those who commit those acts of violence?

“The White Tiger” does not answer these questions in a clear-cut way.

There are no heroes in the beautiful, corrupt capital city of New Delhi.

Another thing to consider about “The White Tiger”: it seems specifically tailored to Western audiences.

Ashok’s American traits make him gentler and understanding, and when he abandons them, he becomes much more like the master Balram has come to expect.

All too common in media about underrepresented groups is the rags-to-riches story. The main character finds success not by fixing the broken system but by finding a way to exist within in it, peacefully or otherwise.

Many aspects of the Indian culture are harshly critiqued, like the cruel matriarch of the family, the servant-master relationship, and the immobility of the caste system, while the more beautiful aspects of Indian culture go unexplored.

The White Tiger raises important qualms with societies based on class systems.

However, not every story about an underrepresented group must be about suffering and hardship. There are still many stories to be told about Indian experiences.

Movies have made huge strides in representation up to this point, but there is still progress to make.

I look forward to consuming the media that allows people to tell their stories without concern about how Western audiences will interpret them.